When you experience loss at a young age, the ephemerality of life becomes a constant companion — a ghost, haunting each moment, quietly slipping in where it’s least wanted. It follows you into the café as you sit with an old friend, whose face, though largely unchanged, is marked by the experiences you haven’t been beside them to share. It lingers in the shadows of your childhood home the last time you walk through it. And it sits heavy on your shoulders as you split that first perfectly ripe peach of the summer, feeling its fuzz tickle your upper lip as you take the first bite — the juice of the other half running down Nana’s chin. You gaze in the window, willing your legs not to buckle as that ghost taunts, “Savor this moment. Take a mental picture. There aren’t many like it left.”

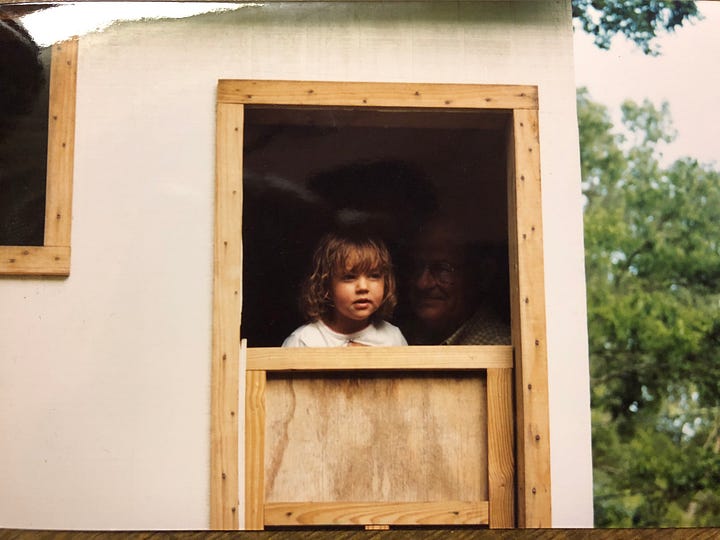

Through the light-backed window, you glimpse your 8-year-old self standing in the pool at the Whaley house, sun-baked and salty, and feel the sticky sweetness of another peach dripping from your fingers into the water you never bothered to leave. You taste the cobbler Tonn made every year, and you hear Poppy tell you how he fetched jar after jar of canned peaches for his mother before she died. And you wonder if not so far in the future, you'll trade places with the woman beside you now, whose hair has only just begun to gray at 85, and introduce your own children or grandchildren to this little joy. If you’ll watch their sticky smiles grow wider as your own memories drip down like the juice between their small fingers.

When I started college, I had a large family and had had the great fortune of never knowing loss. By the time I graduated, I’d lost an uncle, both grandfathers, my maternal grandmother, and my mother. That changes how you think, how you view the world. Death strips you of any youthful whims of invincibility and experiencing so much in such a short time leaves a sense of foreboding in its place. Even the happiest moments for me are now tainted by the knowledge that they, too, will soon be nothing more than a memory; that some time will be my last time to hear Nana’s laugh, my last time to hug her and smell the familiar scent of her specific red Dial soap; that at some point, I’ll walk out a door I’ll never reopen, and it could happen anytime without me even knowing. I could be wrong, but I don’t think the average person lives with such constant fear.

The natural remedy is, of course, to cherish every second, but when you experience loss at a young age, even the most mundane moments take on gut-wrenching importance. The smell of the August air hangs heavy with nostalgia, rendering the veil between past and present no thicker than muslin. It’s as though you’re constantly straddling memory and presence. There’s a tightrope-like duality of acknowledging how fleeting life is, trying to feel and simultaneously commit to memory each and every moment, and yet remaining walled off and distant from the present, jailed by the ghost of your reveries and a sadness at the passing of time. It’s understanding that once you’ve acknowledged the moment you’re in, it’s already passed.

Standing over the sink last Sunday, sharing that first, most delicious, peach with Nana, I wished I had a camera. I wished there was a film crew documenting my every moment, so that when these dreaded somedays arrive, I could roll back the tape and once again see her in her church clothes, always perfectly pressed, once again see the little wrinkles around her lips scrunching with every bite, smudging her lipstick, and hear the sound of our laughter as we drip peach juice all over the counter.

Perhaps had I not known loss so intimately so young, I wouldn’t carry around this constant ache of sadness. Perhaps this ghost wouldn’t follow my every step, reliable as breath. But, perhaps I’d also not have such delusions of grandeur about life’s most mundane moments. Knowing death is the forgone conclusion to all our stories, the only viable option for living is to ward off its nothingness. To try and weigh the joy of eating peaches heavier than the sadness in knowing you’ll never taste that specific one again, and pray that if we’re lucky, when we breathe our final breath, we’ll get to watch these mundane moments all over again.